Back on track to below 2 degrees

Back on track to below 2 degrees

In adopting a roadmap packed with circular strategies, we can pave the way for the systemic transformations needed to course-correct the global economy—going far beyond the limitations of current policy and national climate pledges. The current pledges bring us over 15% of the way; the circular economy delivers the other 85%. If the coming decade is the decisive one for humanity’s future on earth, then 2021 is the year to ramp up our efforts to bring our goals into realistic reach and prevent the worst effects of climate breakdown. Our current economy is only 8.6% circular, leaving a massive Circularity Gap. The good news is that we only need to close the Gap by a further 8.4%—or roughly double the current global figure of 8.6%—to get there.

A circular economy can satisfy societal needs and wants by doing more with less. We need materials to fuel our lifestyles; this produces emissions. However, the circular economy ensures that with less material input and fewer emissions, we can still deliver the same, or better, output. Through smart strategies and reduced material consumption, we find that the circular economy has the power to shrink global GHG emissions by 42% and cut virgin resource use by 28%. Within this, the societal need of Housing delivers half of the impact, while Mobility and Nutrition account for much of the rest. To get to our end goal of a socially just and ecologically safe space, we need intelligent resource management to stem consumption and cut emissions, so their impact falls within planetary boundaries.

This is the real year of truth. With 2020 struck by covid-19, lockdowns around the globe not only contributed to a sharp decline in emissions, but also accelerated decommissioning of fossil assets. Despite this progress being unintended and arguably temporary, it can teach us valuable lessons to translate into structural change—and now, the world seems to be listening. Emboldened by universal uptake of renewables, governments are making decisions that will positively shape our climate future. The events of 2020 also served to hold a magnifying glass to the flaws in our system—an unsustainably linear system reliant on the exploitation of nature and people— and there is no environmental justice, without social justice. Destructive and instructive as the pandemic proved, it is ultimately climate breakdown that will be the biggest global health-threat of the century. In a time of building back better, the circular economy has never been more relevant.

The importance of international collaboration along value chains

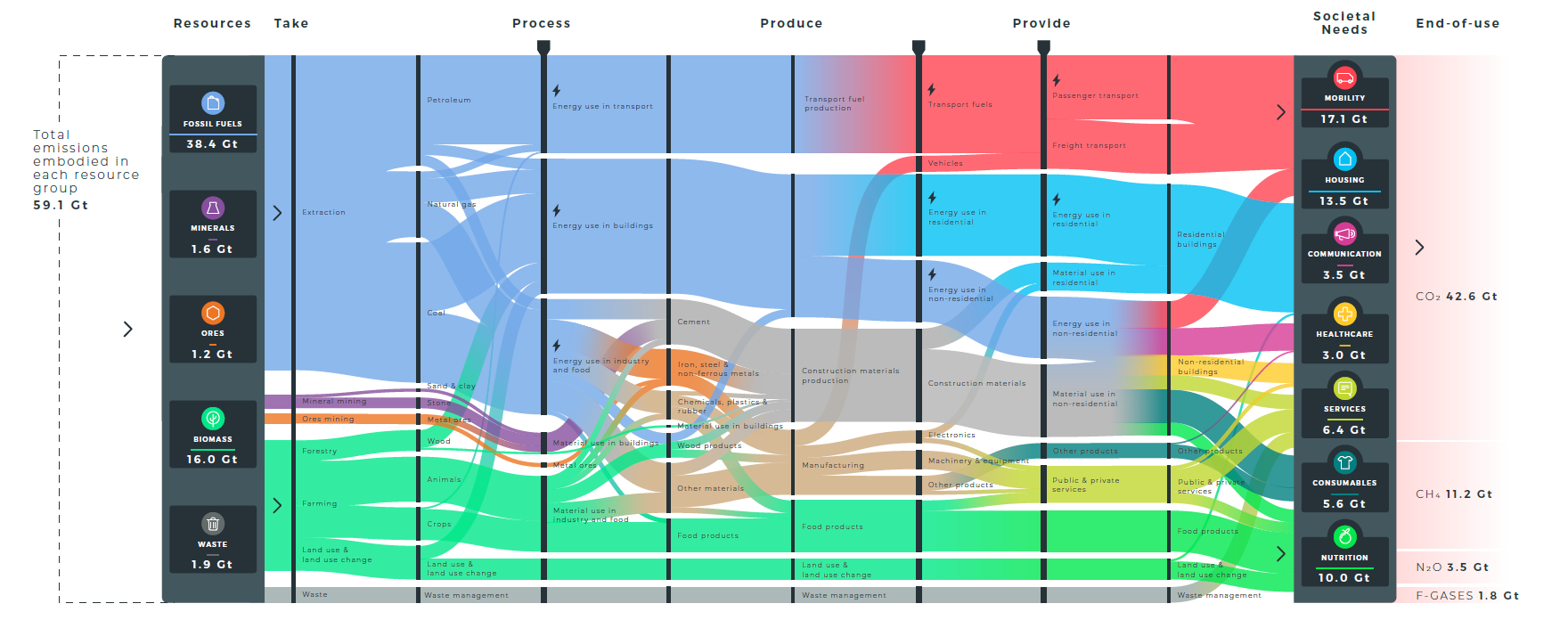

The 2016 publication from Shifting Paradigms on circular economy opportunities in Lao PDR , concluded that 67% of our global carbon footprint is related to material management. This analysis set energy-related end-uses like personal transport, heating, cooling and lighting, apart from material-related uses like the production of food, buildings, vehicles and infrastructure. For the 4th Global Circularity Gap Report, Circle Economy’s research team re-calculated this figure while using the Environmentally-extended Multi-regional Input-Output Analysis (EE-MRIOA) database Exiobase v3.7. With 70% they arrived at an even higher share of GHG emissions which is are ultimately generated through material handling and use.

Combined with the statistic that an estimated 30% of the carbon footprint of nations are emissions embedded in products crossing borders, the necessity for international collaboration to address embedded emissions becomes even clearer.

Targeting embedded emissions in practice

The governments of Vanuatu, The Gambia and Lao PDR are already integrating circular economy opportunities in their second Nationally Determined Contributions under the Paris Agreement. They acknowledge that embedded emissions must be part of their attempts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. For example, the carbon footprint of consumption in Vanuatu (territorial emissions corrected for emissions embedded in exports), is around 57% related to imported goods and materials. For The Gambia, this value is 25%.

Strategies to reduce embedded greenhouse gas emissions often also relate to prioritising domestic and resources or regenerative of secondary origin. This reduces the emissions embedded in imported goods and materials, improves the trade balance and can support domestic economic development job creation. Next to this, many low- and medium-income countries have a waste management system which is ill-equipped to process the waste streams from imported goods and materials.

Identifying circular economy opportunities to prioritise regenerative and secondary materials which improving the lifetime and user intensity of products, requires examining the embedded emissions of materials, and understanding how materials serve specific societal needs. This is what we call a metabolic analysis, whereby not only the flows are examined, but also their impact on the quality of natural assets like forests, agricultural soils, watersheds, marine environments etc.

Mapping a country’s ‘metabolic system’ helps us understand how it uses material resources to deliver valuable services – such as nutrition, shelter and mobility – to its residents and identify opportunities for improvement. Next to this, it helps us prioritise systemic over incremental interventions, step away from sectoral silo’s and look across national borders for the most promising circular mitigation opportunities.

For Vanuatu, this approach revealed a series of opportunities, which target 37 percent of national GHG emissions in sectors other than livestock. They also aim to reduce upstream emissions embedded in imported products with over 35,000 tCO2e and target avoiding over 28,000 tonnes of solid waste per year, or 44 percent of the total.

Shifting Paradigms is one of the lead authors of the Global Circularity Gap reports.

Client: Circle Economy

2020-2021

Photo credit: Photo by Taylor Rooney on Unsplash