The world can maximise chances of avoiding dangerous climate change by moving to a circular economy, reveals a joint report with Circle Economy launched at Davos during the annual meeting of the World Economic Forum in 2019.

The second edition of the Global Circularity Gap Report highlights the vast scope to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by applying circular principles – re-use, re-manufacturing and re-cycling – to key sectors such as the built environment. Yet it notes that most governments barely consider circular economy measures in policies aimed at meeting the UN target of limiting global warming to 1.5°C.

The second edition of the Global Circularity Gap Report highlights the vast scope to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by applying circular principles – re-use, re-manufacturing and re-cycling – to key sectors such as the built environment. Yet it notes that most governments barely consider circular economy measures in policies aimed at meeting the UN target of limiting global warming to 1.5°C.

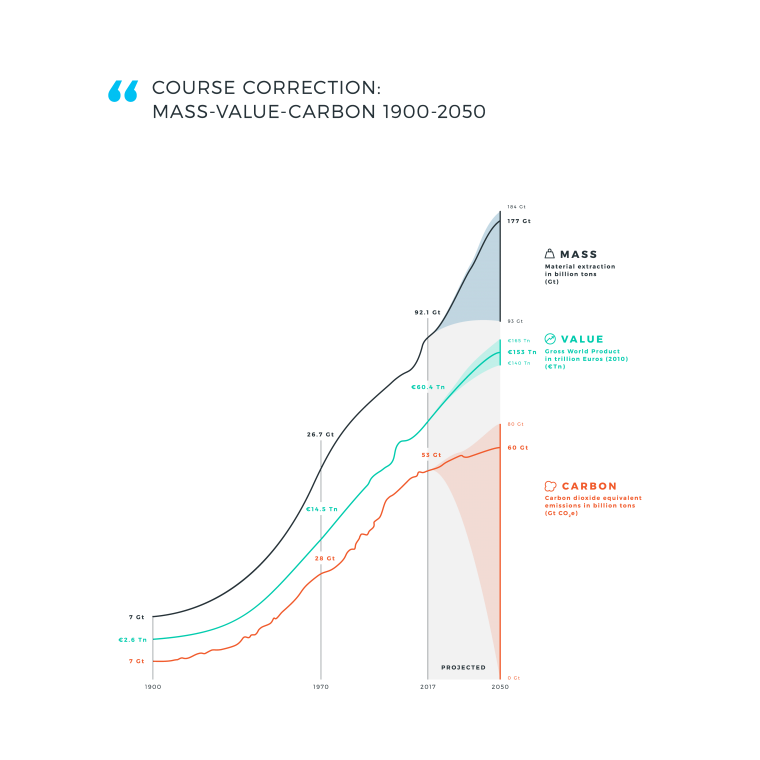

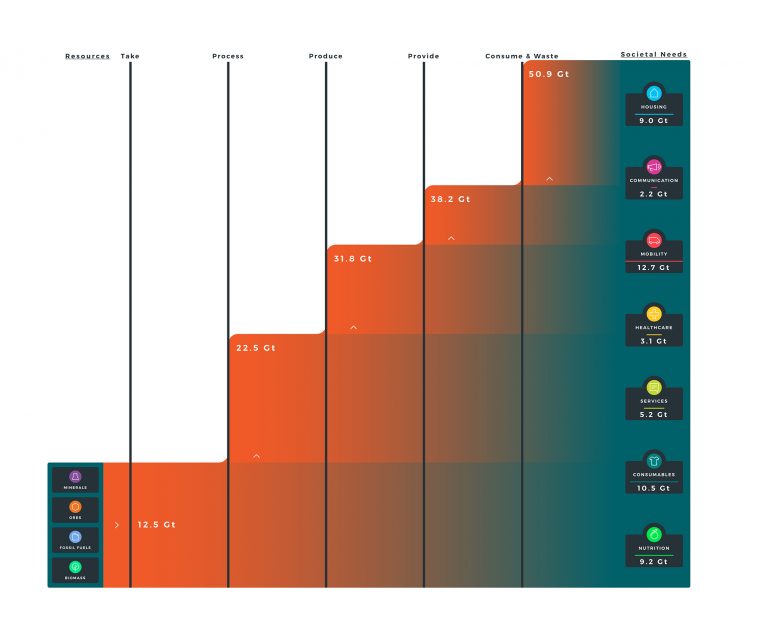

The Circularity Gap Report 2019 finds that the global economy is only 9% circular – just 9% of the 92.8 billion tonnes of minerals, fossil fuels, metals and biomass that enter the economy are re-used annually. Climate change and material use are closely linked. Circle Economy calculates that 62% of global greenhouse gas emissions (excluding those from land use and forestry) are released during the extraction, processing and manufacturing of goods to serve society’s needs; only 38% are emitted in the delivery and use of products and services.1

Yet global use of materials is accelerating. It has more than tripled since 1970 and could double again by 2050 without action, according to the UN International Resource Panel (MaterialFlows, IRP, 2017).

Shifting Paradigms was responsible for the climate chapter, which concludes that a 1.5 degree world can only be a circular world, echoing an earlier conclusion by Material Economics. Recycling, greater resource efficiency and circular business models offer huge scope to reduce emissions. A systemic approach to applying these strategies would tip the balance in the battle against global warming.

Governments’ climate change strategies have focused on renewable energy, energy efficiency and avoiding deforestation but they have overlooked the vast potential of the circular economy. They should re-engineer supply chains all the way back to the wells, fields, mines and quarries where our resources originate so that we consume fewer raw materials (Stanley Foundation, 2017). This will not only reduce emissions but also boost growth by making economies more efficient.

The report calls on governments to take action to move from a linear “Take-Make-Waste” economy to a circular economy that maximises the use of existing assets, while reducing dependence on new raw materials and minimising waste. It argues that innovation to extend the lifespan of existing resources will not only curb emissions but also reduce social inequality and foster low-carbon growth.

Cutting emissions and waste from the built environment

Circular strategies to reduce waste are particularly important in the built environment, which accounts for a fifth of global emissions. Circle Economy calculates that nearly half of all materials going into the economy – 42.4 billion tonnes a year –are used in the construction and maintenance of houses, offices, roads and infrastructure.

The opportunity requires global coordination, as countries will need to adopt different strategies. In emerging economies, where high population growth and rapid urbanisation is driving a massive building boom, the challenge is to adopt building practices which minimise the use of raw materials and consequent emissions.

In China, for example, the majority of houses and roads people will use in the next 10-50 years have yet to be built. Circle Economy calculates that its built environment emits a staggering 3.7 billion tonnes of greenhouse gases every year and is set to more than double in size by 2050, from 239 to 562 billion tonnes of material. While less than 2% of China’s construction inputs currently consist of reused or recycled materials, the report notes that increasing this proportion can make a huge impact on emissions. Promisingly, the recycling rate for construction and demolition waste had increased to 10% by 2015 and continues to rise.

In Europe and other developed economies with a mature housing stock, growth in the built environment is much slower. The report calls on these countries to maximise the value of existing buildings by extending their lifespan, improving energy efficiency and finding new uses for them when necessary. It is also important to increase reuse and recycling of material in Europe’s built environment from the current level of 12%.

Fundamental principles of a circular built environment include:

- Financing and investment decisions which recognise the long-term and future value of built assets;

- Reusing existing building materials;

- Modular design of new building materials to allow for re-use and re-assembly;

- Alternatives to carbon-intensive materials such as cement;

- Optimising the lifetime of buildings and designing them for flexible use.

Three key strategies for the circular economy

The report highlights three key circular strategies which could be adapted throughout the economy and gives examples:

- Optimising the utility of products by maximising their use and extending their lifetime. Ridesharing and carsharing already make it less important to own a car. Autonomous driving will accelerate this trend, potentially increasing the usage of each vehicle by a factor of eight. At the same time electric powertrains, intelligent maintenance programmes and software integration can enhance the lifetime of cars.

- Enhanced recycling, using waste as a resource. By 2050 there will be an estimated 78 million tonnes of decommissioned solar panels. Modular design would enable products to be easily disassembled, components to be re-used and valuable materials to be recovered to extend their economic value and reduce waste.

- Circular design, reducing material consumption and using lower-carbon alternatives. Bamboo, wood and other natural materials have the potential to reduce dependence on carbon-intensive materials such as cement and metals in construction. Instead of emitting carbon, these materials store it and will last for decades. They can be burnt to generate energy at the end of their life.

Recommendations for governments

The Netherlands has set itself a target of becoming 50% circular by 2030 and 100% by 2050, but most governments have yet to wake up to the potential of the circular economy.

The report calls on governments to ensure that climate change and circular economy strategies are joined up to achieve maximum impact, through the use of tax and spending plans to drive change. They should:

- Abolish financial incentives which encourage overuse of natural resources, such as subsidies for fossil fuel exploration, extraction and consumption;

- Raise taxes on emissions, excessive resource extraction and waste production, for example by implementing a gradually increasing carbon tax;

- Lower taxes on labour, knowledge and innovation and invest in these areas. Lower labour taxes will encourage labour-intensive parts of a circular economy such as take-back schemes and recycling (ECF, 2017).

Client: Circle Economy

2018-2019

1 In 2017, total greenhouse gas emissions (excluding land use and forestry) were 50.9 bln tonnes of CO2 equivalent including: 12.5 bln in extraction; 10 bln in processing; 9.3 bln in production; 6.5 bln in delivery of products and services; and 12.7 bln during consumption. Circle Economy, analysis based on: Exiobase and Olivier J.G.J. and Peters J.A.H.W. (2018), Trends in global CO2 and total greenhouse gas emissions: 2018 report. PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency, The Hague.

2 Global use of materials rose from 26.7 bln tonnes in 1970 to 92.1 bln in 2017. IRP, 2019, MaterialFlows.net, Domestic Extraction of World in 1970-2017, by material group.

By 2050 global material use is forecast to reach 170-184 bln tonnes. IRP, 2017, Assessing global resource use: A systems approach to resource efficiency and pollution reduction