Commissioned by the Scientific and Technical Advisory Panel (STAP), which advises the Global Environment Facility (GEF), Shifting Paradigms and Circle Economy have researched how the circular economy can reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in low- and middle-income countries.

This report uncovers the range of environmental and socio-economic co-benefits that circular mitigation interventions can bring to GEF countries of operation and highlights how to support countries to accelerate the transition to a low-carbon circular economy. The report’s findings provide valuable ideas of thematic issues for the GEF to consider in its present and future projects and programmes.

The topic is a very timely one and supports what proponents of the circular economy have long suspected: emissions are inevitably tied to our use of material resources. Circle Economy’s Circularity Gap Report 2021 reported that circular economy strategies—which allow us to do more with less—implemented across sectors and nations, have the potential to slash global GHG emissions by 39%. Earlier research by Shifting Paradigms for UNDP pointed out that as much as 67% of emissions stem from material extraction, processing and handling, enforcing the need for an approach that touts intelligent resource management. In being a means to an end for a socially just and ecologically safe space, the circular economy also holds promise in delivering co-benefits such as biodiversity and job creation.

However, while evidence confirms that the circular economy holds significant potential for emissions mitigation in Europe and G7 countries, its impact on other parts of the world is less known. In these contexts, the circular economy is known by other terminologies such as green growth, sustainable production and consumption, sustainable development and resource efficiency. There are valuable lessons to learn on the application of circular economy principles in low- and middle-income countries, especially as the circular economy is not yet leveraged to its full potential in any part of the world.

While existing mitigation commitments—laid out in countries’ climate blueprints, the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs)—primarily focus on increasing the share of renewables in the energy mix, improving energy efficiency, and halting land-use-related emissions from deforestation, room for improvement exists in the form of circular strategies, which tap into previously unexplored mitigation possibilities. This report makes a case for such strategies in sectors relevant to the work of the GEF including agriculture, forestry, renewable energy and waste, construction and transport. The proposed interventions currently do not play a large role in the Kyoto Protocol’s Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), which is seen as a ‘trailblazer’ of global investments in GHG mitigation—highlighting the further potential for mitigation opportunities that complement measures under the CDM.

The most promising circular interventions for GEF countries of operation

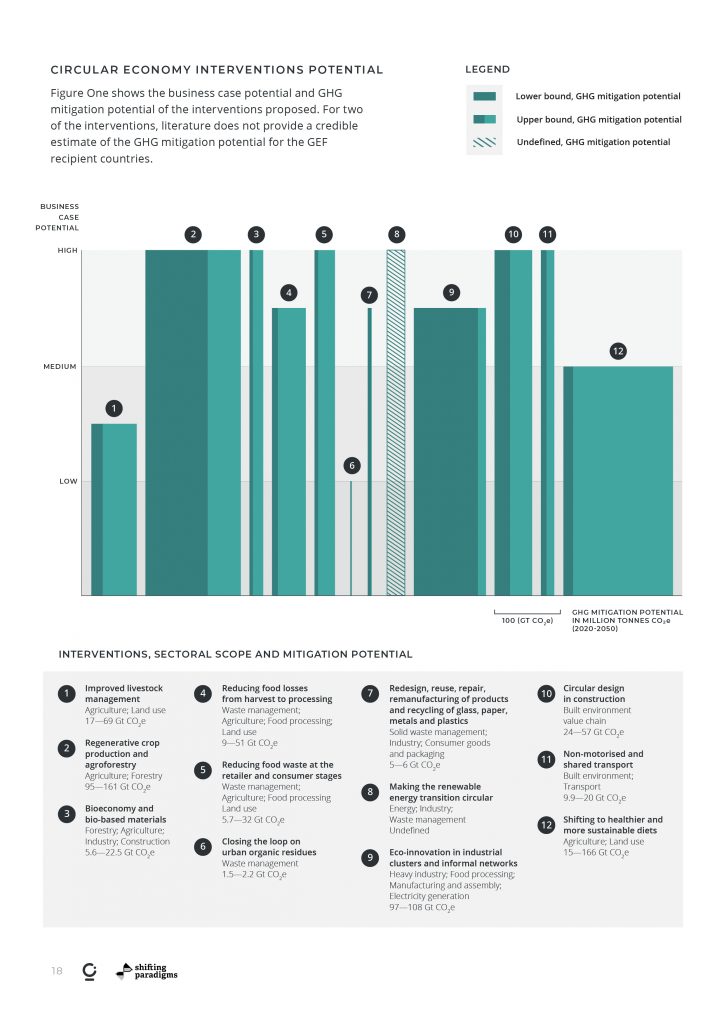

This report presents 12 interventions which may be relevant to the work of the GEF. These circular mitigation interventions were chosen based on their potential to go beyond existing climate action in the GEF countries of operation, and their ability to deliver socio-economic and environmental co-benefits (which are related to GEF’s other focal areas of biodiversity, chemicals and waste, land degradation and international waters). The mitigation potential and business case potential for each intervention, described in more detail in the report, is given by the Figure below.

The proposed interventions are:

- Improved livestock management: Reduce emissions from livestock through productivity improvements, improve manure management and introduce anaerobic digestion of manure.

- Regenerative crop production and agroforestry: Invest in cropland management practices that regenerate soil health, and increase biodiversity and carbon sequestration, including the use of agroforestry and mixed cropping.

- Bioeconomy and bio-based materials: Scale the mechanical and chemical processing of agricultural and forest residues to produce bio-based construction materials (and other industries).

- Reducing food losses from harvest to processing: Enhance harvest methods and timing, and improve the capacity to safely store, transport and process food products.

- Reducing food waste at the retailer and consumer stages: Reduce food waste through improved inventory management, the development of secondary markets for imperfect food products or products near their expiry date and improved value-chain management.

- Closing the loop on urban organic residues: Recover and separate organic residues from urban solid waste and wastewater for composting, biogas production, water and nutrient recovery to support urban and peri-urban farming.

- Redesign, reuse, repair, remanufacture of products and recycling of glass, paper, metals and plastics: Enhance the collection, sorting and processing of materials and recyclables, diverting waste from landfills and incineration to increase the availability of secondary resources.

- Making the renewable energy transition circular: Implement a life-cycle approach to renewable energy generation and storage capacity through design for disassembly, improved repairability, circular business models and the use of recycled materials.

- Eco-innovation in industrial clusters and informal networks: Apply industrial symbiosis approaches to industrial parks and create formal and informal networks to encourage the use of secondary resources across industries.

- Circular design in construction: Design buildings for improved energy efficiency, and minimise waste in the construction process by applying passive design, and modular and offsite construction.

- Non-motorised and shared transport: Prioritise non-motorised transport, vehicle sharing and public transport in urban development.

- Shifting to healthier and more sustainable diets: Shift to healthy diets that bridge the nutrition gap for lower-income brackets, while curbing meat consumption by diversifying diets to include more plant or insect-based protein.

Accelerating the transition to a circular economy

Synergies exist among all the chosen interventions in terms of their co-benefits, barriers and enabling conditions—and as such, projects in GEF countries of operation should work to address these in a holistic way that prevents value-chain spillover or overlooks potential knock-on effects. Overall, the mitigation and business potential for the interventions proposed are significant. If applied, these strategies have the power to keep us on track for 1.5-degrees of warming and limit the impacts of climate breakdown in GEF countries of operation.

Mitigation potential

The 12 interventions have a joint mitigation potential of between 285 billion tonnes CO2 equivalents (CO2e) and 695 billion tonnes CO2e between 2020 and 2050 respectively. Our remaining carbon budget for an ideal scenario—where we limit warming to 1.5-degrees—sits at 580 billion tonnes CO2, highlighting the necessity for circular GHG mitigation strategies.

Co-benefits

As highlighted in the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) 2019 Emissions Gap Report, achieving climate goals will bring a myriad of other benefits in line with the Sustainable Development Goals. As our proposed circular strategies also focus on reducing primary material extraction and waste disposal, these co-benefits are even more pronounced.

Improved crop yields—and consequentially, higher revenues—food security, lower levels of air pollution, economic growth, the creation of fair and decent jobs and greater personal wellbeing emerged as socio-economic co-benefits of our interventions. Greater preservation of ecosystems, habitat protection that allows biodiversity to flourish and reduced water usage prevail as synergistic environmental co-benefits.

Barriers

The common barriers across the interventions emerged in distinctive categories: legal, regulatory and institutional, technological, cultural and economic and financial. The short-term planning horizons of national governments—which may disfavour policy that requires long-term investment and action—surfaced as a significant institutional barrier, as did policy that fails to consider systems-impact and afford attention to the potential knock-on effects of interventions. Cultural barriers were often interlinked with regulatory challenges: a short-term focus, for example, often means that more acute priorities (such as expanding housing stock) may be given precedence over environmental priorities, instead of being developed in tandem. Rising incomes in GEF countries of operation may also lead to increases in consumption, especially due to cultural values that equate material consumption with success, showing a tendency towards consumption patterns and perceptions common to higher-income countries.

Technical barriers are often linked to economic ones: ‘high-tech’ circular interventions—such as those that require internet access or digitisation—may encounter challenges in countries with insufficient infrastructure. Meanwhile, low-tech measures—composting or regenerative agriculture—lack sufficient financial backing to get off the ground. This is especially the case in situations where the benefits from interventions, such as increased revenues or returns on investments, are not immediate. Financially speaking, the patience of funders and viability of circular business strategies were identified as barriers, as was the inadequate pricing of environmental externalities in goods, which fails to monetarily reward the benefits of circular initiatives. Funding circular interventions at scale—especially in the context of multilateral development banks—also poses challenges, while presenting an avenue for GEF projects to make a significant impact.

Enabling Conditions

Enabling conditions were found to coincide with barriers and ultimately boiled down to one key point: the benefits of circular strategies must be made clear to gain traction with decision-makers and those responsible for their implementation. Demonstration projects that show tangible benefits are needed to galvanise change—and communication on these benefits will increase the willingness to adjust, improve and scale policies. The co-benefits identified come back into play, as linking circular strategies to co-benefits that may be of greater political priority—like food security or job creation—may both inspire and enable swift action. To this end, all stakeholders should be involved in the policy creation process, matched by efforts to raise awareness, provide education and training and analyse how solutions can encompass all aspects of the value chain.

Additionally, standardised data collection and formalised insights on the drawbacks of the linear economy—presented along with the advantages of the circular economy—are crucial to advance circular solutions. Collection and analysis systems that provide detailed data on resource flows and feed them into reporting systems could both enable policymaking, and identify areas where circular strategies could benefit GEF countries of operation.

Next steps

Based on the findings above, the report presents 12 recommendations for where GEF could direct its efforts in implementing circular projects with GHG mitigation potential to get us on track for 1.5-degrees of warming. We find that the GEF is well-positioned to take on such a task—already dedicated to taking value chain perspectives and operating at the level needed to drive systemic change. The report provides tangible recommendations, highlighting the importance of a systems-based, highly participatory approach—involving donor countries, the private sector, businesses and communities—that will demonstrate the far-reaching impact circular strategies can offer.

While the proposed recommendations were developed in the context of the GEF, they are also applicable to other actors in the circular economy. The report finds that it is paramount to combine policy interventions with project support—for example by covering the cost difference between linear and circular approaches for a good or service—which can crucially prevent negative rebounds. It also emphasises the necessity to consider the embodied emissions in products that cross borders, in particular since these products are responsible for up to 30% of a country’s consumption-based carbon footprint. Prioritising local materials, in an effort to both slash transport emissions and involve all actors along value-chains in project design, was also recommended; as was targeting and involving micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) along with the informal sector, which represent a large share of the labour market in GEF countries of operation. Finally, as finance was found to be a significant barrier, the report recommends the GEF to tackle this challenge by implementing circular principles in its own procurement process, as well as developing cooperative and blended finance mechanisms to support and de-risk early investment in circular initiatives.

Client: Scientific and Technical Advisory Panel (STAP)

Partners: Circle Economy

2020-2021

Photo credits: Fern: Daniil Silantev on Unsplash